INTO IT (a novel) Chapter 1: Adam

The experiment is my idea. In his garage John and I will tape a large Amazon box into a terrordome for juvenile mice.

“This is going to be sick,” I say.

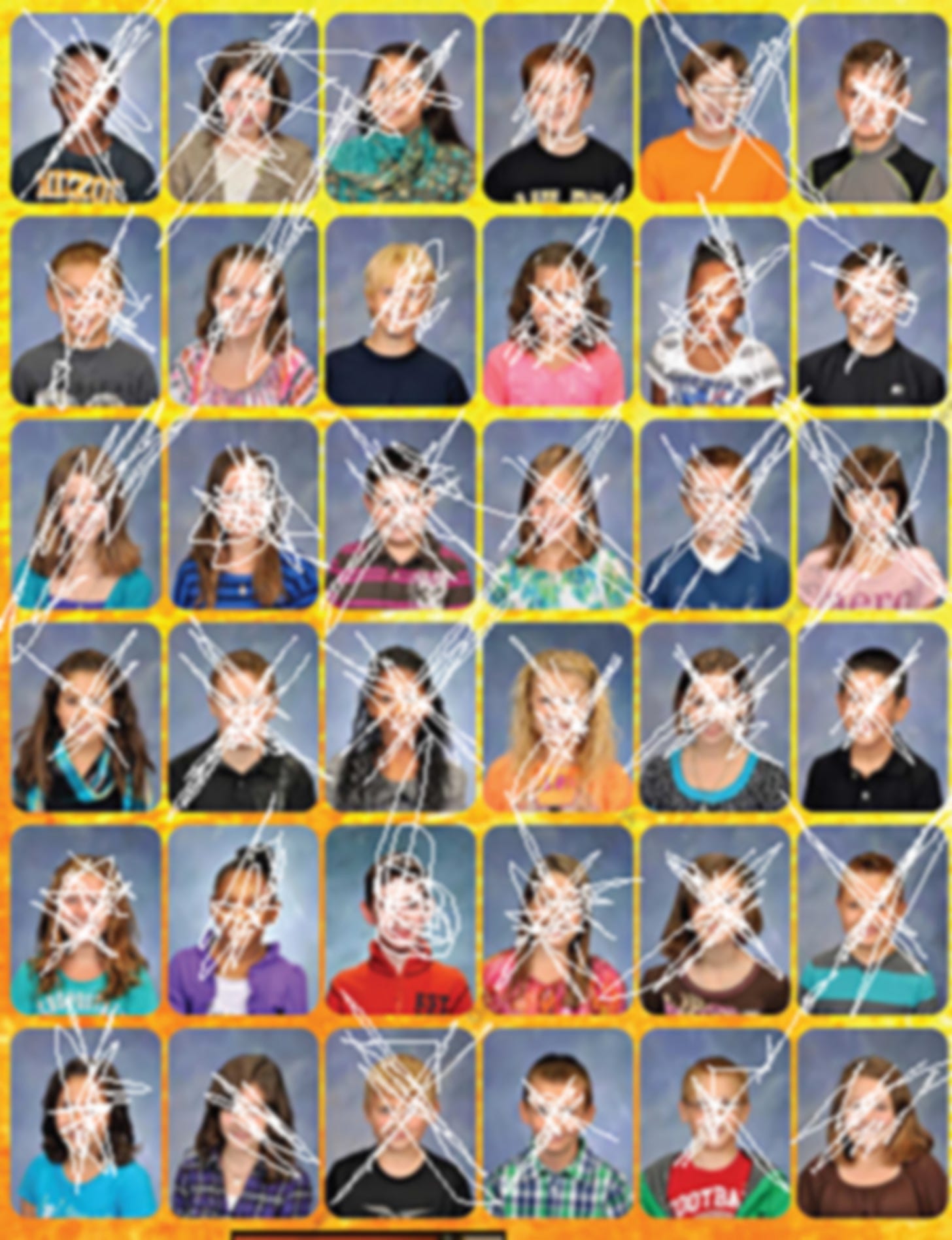

John’s parents are out. Dirty daylight passes through the windows of the garage door. It smells of motor oil and it’s stifling, hot as I always forget it will be when another high school year begins. Last week, our school emailed us a list of shit to buy, such as color-coded maps of worldwide animal extinctions, which they put under a column on the list labeled “Required.” I hadn’t thought our teachers had a sense of humor.

John Teller is tall and skinny, very skinny, as though his parents haven’t been feeding him. His light brown hair reaches his shoulders. He doesn’t look Christ-like because he’s into T-shirts of anime rape. Now that it’s the end of August, John’s sanity is low and his hands tremble. It’s a side-effect, he says, of the medications he says he’s taking. He has one green eye and one grey. I like asking him which one is evil today.

Walking the school halls you’ll not see me, the invisible Adam Davis at five feet seven inches and 310 pounds, a morbid fuckwit. John and I live outside everyone’s circles of concern. Watching and waiting, I like to think.

John bought the mice in the lot behind Walmart. For a charge, deplorables may return their pets’ babies when they don’t want to drown or stomp or freeze them themselves. So, the mice had only one or two days left on the clock.

My procedure will be to set the mice loose in the box, then throw in John’s cat. I will stand back and stand by, ready to swat down the ones that attempt escape.

John murmurs curses and fights with the cardboard and the tape and himself. When he steps back, the box stands three feet tall, leans to the side. I’m not sure the mice won’t leap out, and I’m not sure I’m quick enough to knock them down, but it won’t matter, because if some do get out we will hunt them throughout the garage and beat them with our flashlights.

“Throw them in,” I say.

“I don’t know,” John says.

The lid of the shoebox is secured by white surgical tape, but John’s not peeling it back. He’s sweating, hypothetically from his meds.

The scrabbling sounds coming from inside the shoebox interest me. I’m eager to see the mice twitch. I take it from him. The box shifts in my hands as the mice tumble to one end, then scramble to return to some kind of mouse equilibrium. They’re interesting to me, animal behavior and psychology. I want to see how the rodents will run around in the terrordome. I rip the tape and remove the lid. They are humped shapes swarming, bumping and climbing over each other. Their squeals remind me of the hive members buzzing in the school halls, as they play out their roles during their final days.

“Listen to them.”

“Adam,” John says.

I think, from his tone, that he means, don’t do it.

“This is sick,” I say.

“Okay.”

Never any problem with saying okay.

I give the shoebox three hard shakes, turn it upside down over the cardboard box. A tumbling and a pattering of twenty-four or whatever number of feet, of paws, on cardboard. The mice swarm over each other like living cotton balls, pulsing, one-minded. None try to jump out, so I toss the shoebox and lean over the scrum.

“Look at it.”

“Yeah,” John says.

“Sick,” I say.

The mice have scattered, climbing over each other, some three-deep. They bury themselves into the corners.

“Get her in there,” I say.

I ignore John’s shuffling from side to side. I don’t want to pick up John’s cat and take full control. She’s John’s, and I want to involve him in this.

John regards the box with an expression I don’t recognize. It’s disgust or annoyance at me for telling him what to do. Frankly, I’m done with running our show, picking where we’re going sit under the football bleachers to try to have a cigarette, or devising experiments.

“I don’t know,” John says.

“Get the cat,” I say.

I knew John wouldn’t be up to this without me. Before he’s aware of them I’m at his thoughts with my scalpel.

“Okay,” he says.

Okay. John returns from the kitchen with his twenty-pound tabby cradled in his arms, lolling like a loose, dead cat. Every time I see Unlucky I want so badly to punch her fat stomach that my teeth grind together. John’s father backed over her with his car tire when she was a kitten. She drags a rear leg behind her and cannot jump onto the couch. According to John, he doesn’t help her get up. But I have seen him, even in his times of crazy, help his cat up onto the couch.

Unlucky rolls and pushes out of his arms. Despite her bulk, Unlucky lands in the box on her feet. She sees the mice. She arches her spine, and her legs, even the lame one, shoot to the four corners of the box to pin the mice into the corners. But the mice aren’t easily gripped, so they spill around her claws, pouring under and over each other. They leap onto the cat’s back to escape her claws.

I’m in the movie. It feels false, but also good. I wish there were someone else here to see us. But around other people I’m nothing.

“Sick,” I say.

There’s nowhere for the mice to escape. Still, they make their motions of flight. They run in circles. Unlucky spins along. It’s like the movie, and the scene makes me laugh, but at the same time it makes me a little bit serious. Unlucky claws and drags two mice toward her so she can lie atop and smother them.

John reaches into the box. He tries to lift Unlucky, but I grab his wrist. I lean my considerable weight on his arm and force him to his knees inside his own garage.

“Don’t,” I say. “It’s beautiful.”

The cat warbles in her vicious pleasure.

“What if someone saw us doing this?” I say.

“They’d say you’re sick,” John says. “Congrats.”

“But you’re the real deal,” I say.

I want to make John laugh, because the idea that he’s dangerous is ridiculous. His rages don’t last long enough to make him a threat. I can talk him down with an extra hour of gaming.

Unlucky’s teeth puncture a mouse’s neck. A dollop of blood pops out. It’s weird that mice bleed blood bubbles, while people bleed liquid. In Unlucky’s mouth, the mouse twitches. She would do them all if she could, but I want to see the mice scramble. I pull the cat out by the scruff or whatever of her neck and set her on the floor. Unlucky slinks to the back of the garage where, in the shadows under the tool benches, she can finish off her prize. The remaining mice tremble and shit in shock. One drags its rear left leg, just like Unlucky does. So, John’s cat has taken her revenge on John’s dad, on having to be helped onto the couch, and on the universe by mauling, decapitating, and devouring. I am pleased with the results.